My wife had died four years earlier – just one month before the marathon which would have been our first. I had trained like crazy for about a year. A dearly loved aunt had flown to Houston to be with my three little kids while I ran the marathon. The very few stars in my then film-thin firmament were starting to align; but my children (10, 8 and 6 then) didn’t want to go to the Expo, they wanted to see the Aquarium.

In the aftermath of any defining moment in our lives, we often try – for good or bad —to make sense in retrospect and pinpoint when and how it all started. And while I say I had trained my butt off for almost a year, the most persistent memory of those months, which ultimately were supposed to qualify me for the Boston Marathon, takes me back to the track at my youngest son’s high school. Early in the morning, the familiar lyrics started whispering the music in my ears, saying first there’s nothing, but a slow glowing dream your fear seems to hide deep inside your mind; and then the speedwork started: 13 x 1600 with 90 seconds rest in between.

Months later, in Houston, I eventually convinced my kids (or bribed them, I just can’t remember – there’s an image of the Aquarium embedded there somewhere) to go to the Expo to get my bib.

My older daughter was understandably concerned. I had told her a couple of times before that on rare occasions people die while running marathons; and having lost her mother a few years back, her face was lit up like a Christmas tree when she saw me (alive) at the last stretch of the marathon. And that is the only thing I remember about that race.

Although I clocked better times in two marathons (3:04 in San Francisco 2004 and 3:02 in Chicago two months later), when I crossed the finish line in Houston as the clock marked 3:11, I felt my life had changed at some level. I had qualified for Boston.

I think in all honesty there are very few equalizers in life (truly equalizers): death, faith, sex and the Boston Marathon qualifying times. We are all the same when we are filtered through those unforgiving concepts.

By the time I qualified, I had been running for seven years and had run my first marathon in 2001. And by then I thought I had grasped the mystique of Boston. After all, I had qualified.

But I was wrong.

That thought was shattered the moment I stepped out of Boston’s Logan Airport after a long trip from Ecuador; and the cab driver took a look at me and said “You came to run the marathon.” Surely, it was then I knew I had grasped the mystique. But, guess what, I was wrong again.

It wasn’t at the Expo either. Although it was then I had to fight back the tears for the first time.

The second time I had to fight back the tears was at the starting line, a couple of days later, conscious of the privilege. But it was easier then not to hold them back too much, since I was not the only one in such endeavor.

It was a very hot day. That is a heavy statement, mind you, coming from someone who lives in Ecuador and runs almost all the time in temperatures over 90 degrees and in humidity over 90%. There is a small snippet of how hot it was, in a story I wrote years later as a tribute to the race after the tragedy of the bombs.

The race was glorious: hot, but glorious. I wasn’t going to set a PR, I didn’t want to. Prepared as I was, I just wanted to enjoy the journey (the girls from Wellesley were a fantastic distraction). As I was running, suddenly, I started to feel a change in the atmosphere People around me were talking to themselves, saying things like “here we go,” “this is what you trained for,” “this is it,” and I was utterly confused Had I missed something? I had no idea what was coming. Then I saw it, just past the fire station: the start of the hills.

I was so subdued by the idea of Heartbreak Hill that I lowered my pace and hoped for the best. There was no way this race was going to break me after everything I had done to win the right and the privilege to run it. Fearful, a few miles later, I asked another runner where was Heartbreak Hill. “We just passed it,” he said.

But the heat and my wet shoes from the water of the firemen hoses – yes, it was hot; I believe I’ve said that before—took its toll. I had blisters on both my feet for the first time in my running career.

But I was not going to break down.

Wrong again.

That was the moment (not during training, not when I qualified, not at the airport, not at the Expo, not even later when I lived for years knowing my marathon times were well within qualification standards), that was the precise moment when I understood, when I finally grasped the mystique, the allure, the je ne sais quoi that imbues the race.

It was mile 24 and I started walking. The crowd was delirious, the Red Sox were playing the Yankees a few blocks away (or was the game over by then?) and I veered towards the sidewalk and sat down. I wanted to be at Fenway, I wanted to be singing Sweet Caroline and drinking a cold one (marathons will do that to you eventually).

Bad move, but a very, very good move in hindsight.

The roar of the crowd was deafening, and it was directed to me! Oh my God, I thought, these people are yelling at me. I thought I had done something wrong (as a matter of fact, I did something wrong, but – as things tend to go in life — I wouldn’t understand it until later). When I finally navigated through the noise and focused on words and gestures I understood everyone was telling me to get up and run. Particularly one fellow – who now has become a mantra of my running days, whoever he is — who looking me in the eye, pointed at me and ordered “You are going to get up, and you are going to run to that finish line.”

Of course, there was no other option in the universe but obedience.

And I did just that.

And when I crossed the finish line on Boylston there was no longer a reason to hold back the tears.

Nine years later, I cried again during the 2013 Boston Marathon, but miles away and for a whole different set of reasons. Let me share my thoughts and reaction to the bombing tragedy:

Being from Ecuador, I was probably one of the few among the approximately 20,000 people toeing the line at the Boston Marathon in April 2004 who was not worried about the heat. But when I sat down on the asphalt to wait for the starting gun, I had to get up immediately because I burned my ass. So much so that this morning, nine years later (after donning the same pair of shorts in which I ran the Boston Marathon in 2004), if you know where to look, you can still find the black stain of melted asphalt at the rear end.

I have been running for over 16 years, and in that journey of discipline and dedication, I have found catharsis, joy, pain, disappointment, frustration, triumph, bitterness, failure, and every once in a while, blood in the urine. I have run in the sun and in the rain, I’ve run with snow, with wind, and in such cold weather my water bottle froze after 20 minutes.

I have run alone more times than with company. I have run laughing, singing, while sick, with nausea, bleeding, and I have run crying. I have run for the living and I have run for the dead. In my runs I’ve made friends, and also found out those who were not my friends. I’ve chartered professional strategies, I’ve reached agreements with lawyers of the other party, I’ve bought – and eaten while running— many a hamburger, I’ve listened to dozens of books (but no more than 40 songs), I’ve urinated in public – even next to a police patrol car in Detroit — and every once in a while I’ve thought to have found the formula to fix the world; and rarely have I been so wrong.

Today I ran ten miles with the same pair of shorts that have the asphalt stain at the rear end. I ran in memory and solidarity of those affected by the catastrophe at this year’s Boston Marathon. Today I ran for Boston.

Since 2006 (when I started logging my runs) I’ve found I have run enough to circle around the world twice, and then some. I have run weeks of 120 miles and weeks of 20 miles. I have run 15 marathons. I have trained endless hours with the only goal of qualifying to Boston. I’ve had unbelievable speed sessions at dawn at the track of my son’s school, with 13×1,600 repeats @7:20 average pace and 90 seconds rest in between. The total of all these miles has allowed me to qualify for Boston only five times, and of those five opportunities – for matters to be blamed on the calendar or travel issues — I have only run that illustrious race once.

Boston is the Holy Grail for runners. The Olympics aside, it is the only race that admits only runners who have previously qualified in another certified marathon, achieving extraordinarily demanding times for their age group and gender.

Some time ago, a retired engineer, who was also a runner, analyzed the results of 227 marathons in the U.S., and came to the conclusion only 10% of runners achieved their qualifying standard for Boston.

Only a non-elite runner can understand how challenging the qualifying requirements are, but it is their challenge that gives Boston its mythical and mystical aura. Runners even joke the only benefit of getting older is that every five years your qualifying time decreases by five minutes.

It is true that in the Boston Marathon there are some slots for people who want to run for charity – without the need of qualifying, but having to raise large amounts of money — but the purist runner, though fully supporting these initiatives, does not talk too often about that.

That which makes the Boston marathon so emblematic cannot be explained, it has to be lived, experienced, felt; and time and again, for the Boston runner, that feeling is accompanied by emotional tears of conquest which one stoically fights to repress in public, until the moment one realizes he is not the only one in tears.

Because of that and so much more, it is excruciating for me to bear witness to what happened at the Boston Marathon in 2013, a result of evil and cowardice. It is deeply painful that Martin Richard, just eight years old, lost his life, as well as the other deaths, and the wounds to over 100 people.

As a man and as a runner, as a member of the subculture of those of us who rise early, sweat and sacrifice ourselves (and believe that if we train hard enough for eight to ten months, maybe we will qualify for the next Boston Marathon) I remember the words of the poet John Donne: “No man is an island entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main; if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as any manner of thy friends or of thine own were; any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind. And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.”

Today I ran for Boston.

Emilio Romero

Guayaquil, Ecuador

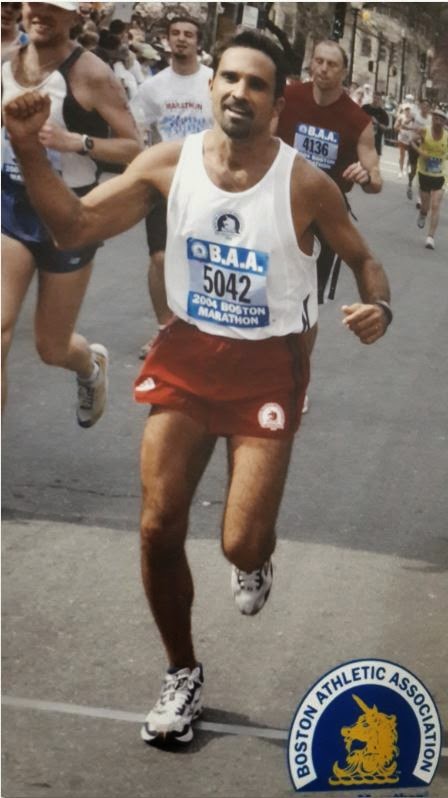

April 19, 2004

Age – 39

Bib # 5042

3:37:22